Travel Journal, 101

Over 20 years has passed since that first jazz session at the small coffee shop in Cody, Wyoming.

My mind brought this memory out of long-term storage, wiping away the dust. And as I think of it, I’m caught by the little details: the way each player looked at each other for ques, the lights of the room, smells of coffee, a dessert from a restaurant that’s probably now out of business, and the tisk tisk tisk of Ronnie’s snare.

I’m also caught off guard by what eventually influenced my musical tastes. If you would have asked me 20 years ago which music I thought would be important to me, I’m sure I’d have said classic rock or something modern and popular.

But that first live gig sank its roots deep.

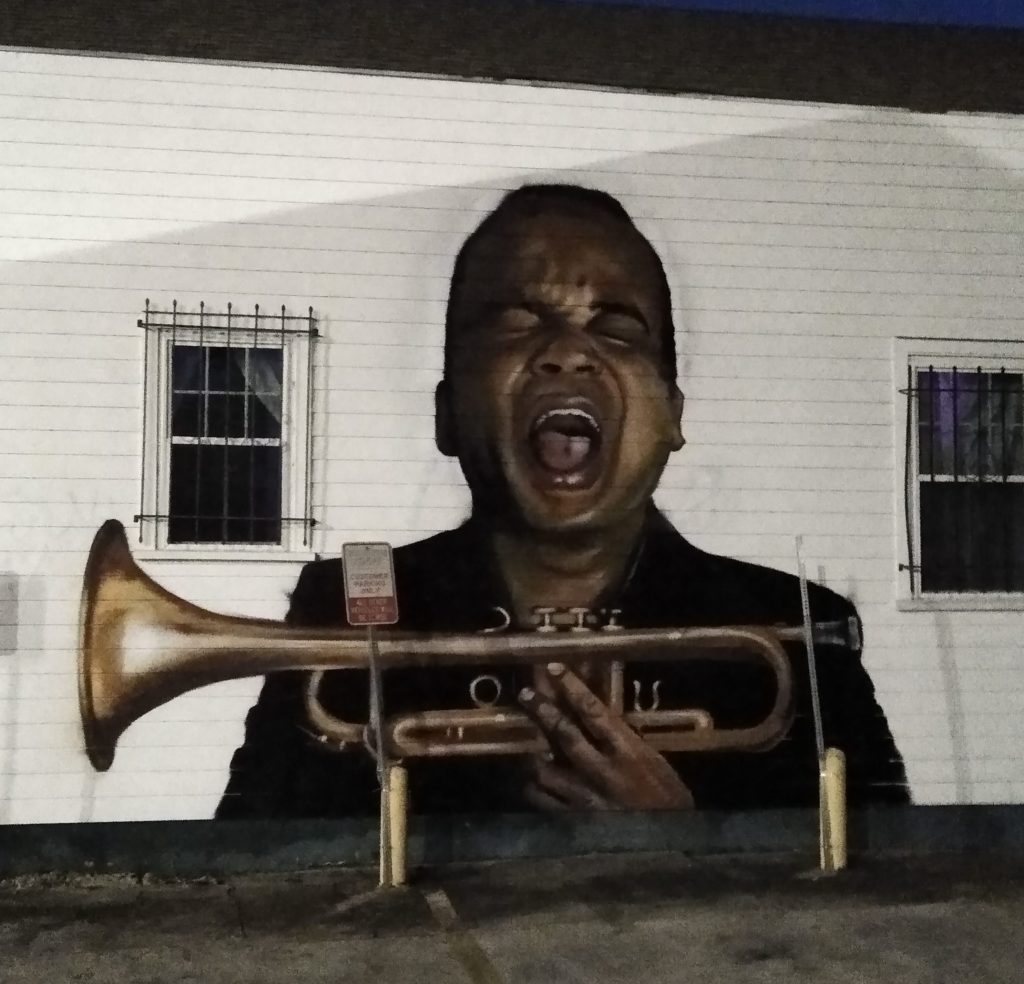

So now, here I am, flying to the birthplace of jazz, New Orleans. I feel like an Imam going to Mecca for the first time.

Where it all began.

It can be easily argued that Jazz is only distinctly American form of music. The Deep South was the home to more slaves than anywhere else in the US. South of the Mason-Dixon line, nearly 95% of all Black Americans suffered as slaves. But the Civil War ended and Lincoln declared all slaves freed. Former slaves, now full American citizens, began the slow move from the South, migrating from the pain. But many stayed. African culture and music flowed freely all over the South, especially New Orleans. Prior to the Louisiana Purchase, New Orleans was home to Spanish, French, and a plethora of refugees.

Over the years, colonial European music began to mix into a bouillabaisse of African culture and European Umpapa beats, creating an original music style. African drum styles clashed with European horns. Instead of musical civil war, hot romance followed.

Jazz was born.

And now, here I sit—at a small club on Frenchmen Street. The lights hang low once again. The band on the stage is giving it their all. Their music belies the funky jazz of the seventies—like they’d been snatched by a bright purple-light-show-time-machine. They play with the passion of a band that may never play again. An end of the world show.

The young man behind the drum kit plays just as tight as our dearly passed Ronnie Bedford.

An electric keyboardist dances as he plays, sweat dropping to the keys.

And after a powerful eyes-shut-solo, the saxophonist cracks open the spit valve and pours out the condensation—it splashes to the floor like the elixir of life.

Nobody can sit still. It’s an all-out brawl of instruments, fighting and dancing with each other.

“But I don’t really like jazz,” you may say.

And you may not.

Jazz, for me, analogizes life itself. Turn on the closest radio or your favorite stream. Most popular songs, country, rock, ect, speak a simple worldview and wrap it up in three-and-a-half minutes. Sure, they’re catchy and fun. But it’s simple; love songs simplify love, war songs simplify war, even Christian music simplifies Christianity, and country songs simplify everything.

But jazz hints at something deeper.

It’s rich and complex.

Often difficult to understand or catch.

Dissident and blue and wild.

Detailed and unresolved.

The worldview of jazz says, “Strap in and hold on. We’ve got something to say, and it ain’t simple.” The worldview of jazz is complex and nuanced and continuous.

Cultural critic and commentator, H.L Mencken once said that, “for every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.”

Few people desire complexity and nuance. Most want their songs to wrap up in three-and-a-half easy minutes. And most want their life to be clear and simple. Unfortunately, it won’t be. No matter what the radio says. And when it isn’t simple, we’re astounded and shocked. And why not? Every song we’ve heard has lied to us.

Jazz won’t lie to you. It’s far too honest.

The rewards of embracing complexity, grant the listener a powerful musical and life experience. Answers shall be found in the deep magic of random Thursday night jazz sessions and dripping saxophones.

So, we sit here, relishing in all the beauty of jazz in the heart of New Orleans, because jazz is life.

Life is jazz.

anthony forrest