Travel Journal, 114

I have been lonely occasionally in my life. Though for the past decade and a half, the perfect companionship of my wife has easily pushed away those feelings.

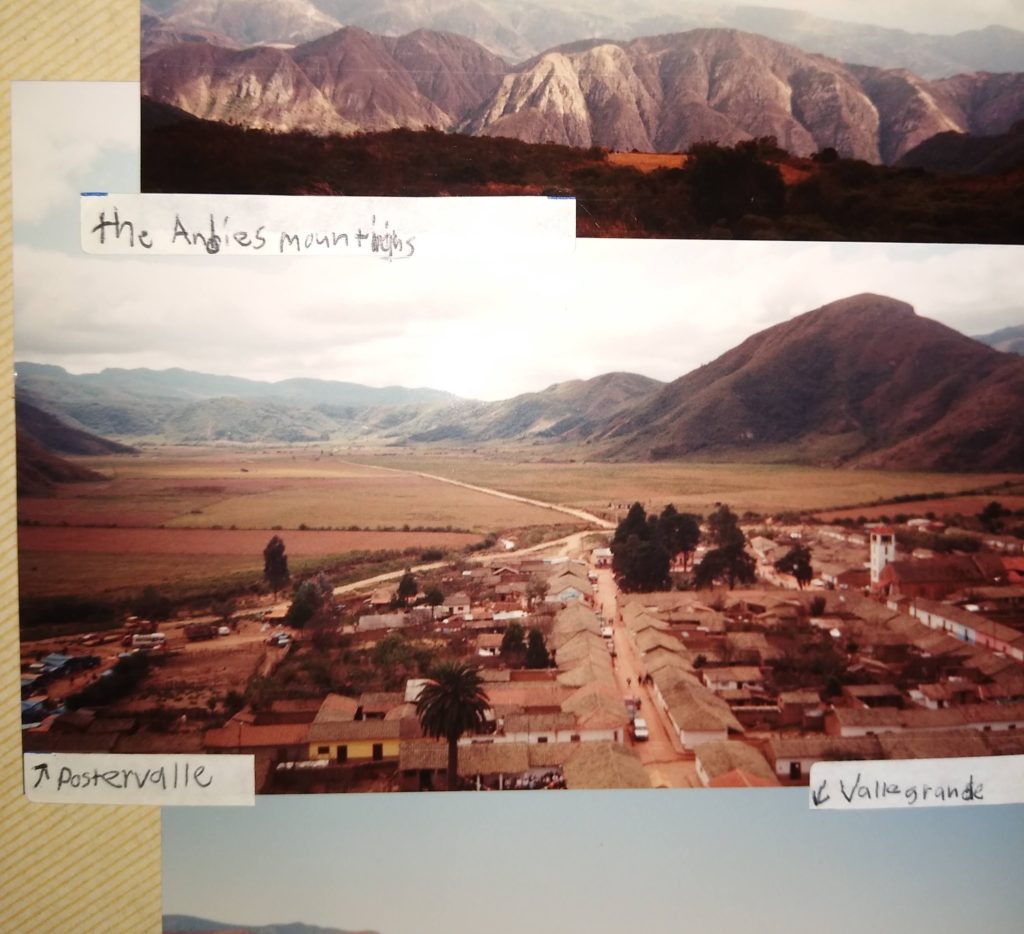

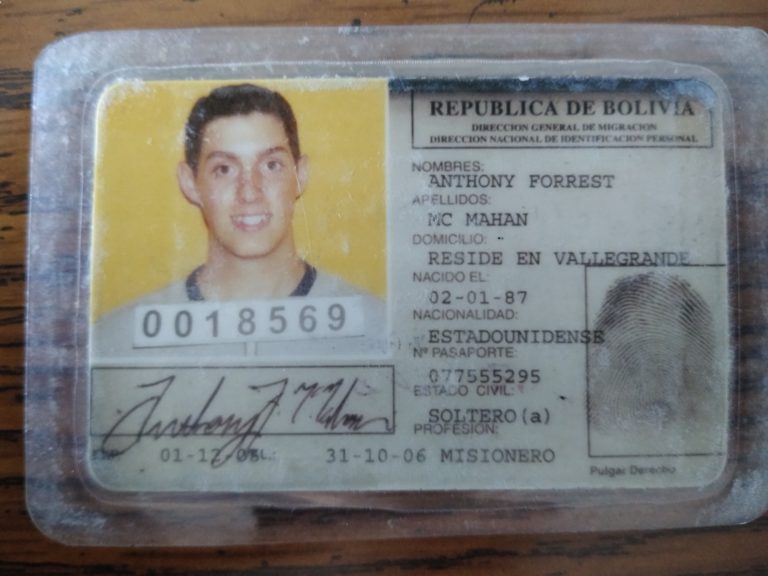

But 17 years ago, I spent the better part of a year in the mountains of Bolivia. That time formed and shaped my life into what it is now, or at least greatly contributed to it. I lived with a few missionaries and other English-speakers for several months. And soon, some of them left to go back to the States for a while. I was left on my own, helping to look after a dairy farm owned and run by an American missionary.

My days were filled with occasional things farming. I milked a few cows, planted a bit of corn (by hand, dropped into a planting tube on the back of an ancient tractor), helped to maintain the water tower, and fought for my life against the evil of South American spiders.

Other Americans lived in the nearby town of Vallegrande. I saw them several times a week. But not always. The traveled around the area doing their own thing. And every couple of weeks, I walked into town and caught a bus (microbus-pronounced meecrowboos). After a relatively uncomfortable ride for three hours, the bus finally pulled into the Andes Mountain village of Pucará. American friends of mine lived there, teaching the Bible and raising four crazy boys (He now pastors a church in Montana where his family also has one of the largest goat farms in the State—it is as cool as it sounds). I relished the time I could get to their home and rile up their kids and eat their food.

But I wasn’t always able to go. Weeks would go by during which I would speak no English (my Spanish is terrible) nor see other expats. I was a stranger in a strange land. I remember waking on a Thanksgiving morning with plans to take the broken down 1975 Honda Super Cub into Vallegrande and have Thanksgiving dinner with an American family. It took me a minute to register the sound of heavy rainfall on the tin roof. I peaked outside and saw a raging downpour. No trip to town today.

I dressed and ran from my room, through the courtyard of the hacienda-style home, to the kitchen. My Thanksgiving would consist of oatmeal and coffee mixed with sweetened condensed milk. I felt a vague nagging at my heart. I was much too young to know what it was that I felt. Youth misses so much. Or maybe time gives us eyes to see. Either way, I know now what deep loneliness feels like. It’s an uncomfortable restlessness of uncertainty. It’s a nagging sorrow which can’t really be understood when you’re going through it. I spent my day sitting in the kitchen, listening to John Denver’s Fly Away, playing my guitar, and reading. Today, that sounds like a glorious afternoon. But then it felt like milquetoast. Loneliness, longing for the company of someone who understands your context and being, turns the good things into white gummy paste.

And I was only in Bolivia for the better part of a year. These feelings of loneliness and separation come to a head when an expat comes back to the States. It took me quite some time to feel like I was an American again.

I have expat friends who’ve experienced this far more than I. They feel a “cultural homelessness.” The idea is that as an American goes to another country to live or work, they begin changing to adapt to that new culture. But they are American and will never truly lose that. So they remain an outsider, no matter how much they change. And what if they go back to the States? They’ve become an outside there as well. They’ve lost a little (or a lot) of their own culture and adhered to another.

If the American is blue and the new country is yellow, after a while, the American turns green. He’s no longer blue and he’s no longer yellow. He’s a little bit of both, mixed together. He’s culturally homeless.

“Wow,” you say, “this is terrible. Why would you tell me this? People should just stay home then! Why would I want to go anywhere or see anything if I’m just going to be changed into a lonely green blob?!”

Because green isn’t all that bad.

The world needs more green people. Green can converse and understand the cultures of blues and yellows. These third culture people tie into the cultures of others. They inevitably speak two or more languages. This type of mixed identity fills the seat of the UN, sends ambassadors to foster peace deals, teaches the Bible in other languages, ends racism in the US, forms agreements for the safety and security of mankind, and loves their neighbor as themselves.

But as the great philosopher, Kermit the Frog once proclaimed, “it’s not easy being green.” The loneliness of travel can often be unbearable. Understanding simple things about a culture is exhausting. Just eating strange food strikes fear into many Americans. Try driving on the wrong side of the road; then come back to the States and get behind the wheel—lookout world. Talk to people; try not to offend them; be the butt of jokes when you make a language mistake. It’s lonely.

Kermit also said that, “green is the color of Spring, and it can be cool and friendly-like.” The rewards of travel greatly outweigh the woes. I have a friend who is moving back to Southeast Asia in a couple of weeks. To him and all the other brave souls out there building a better world, I say, “cheers!”

“You look beautiful. Green is definitely your color.”

anthony forrest