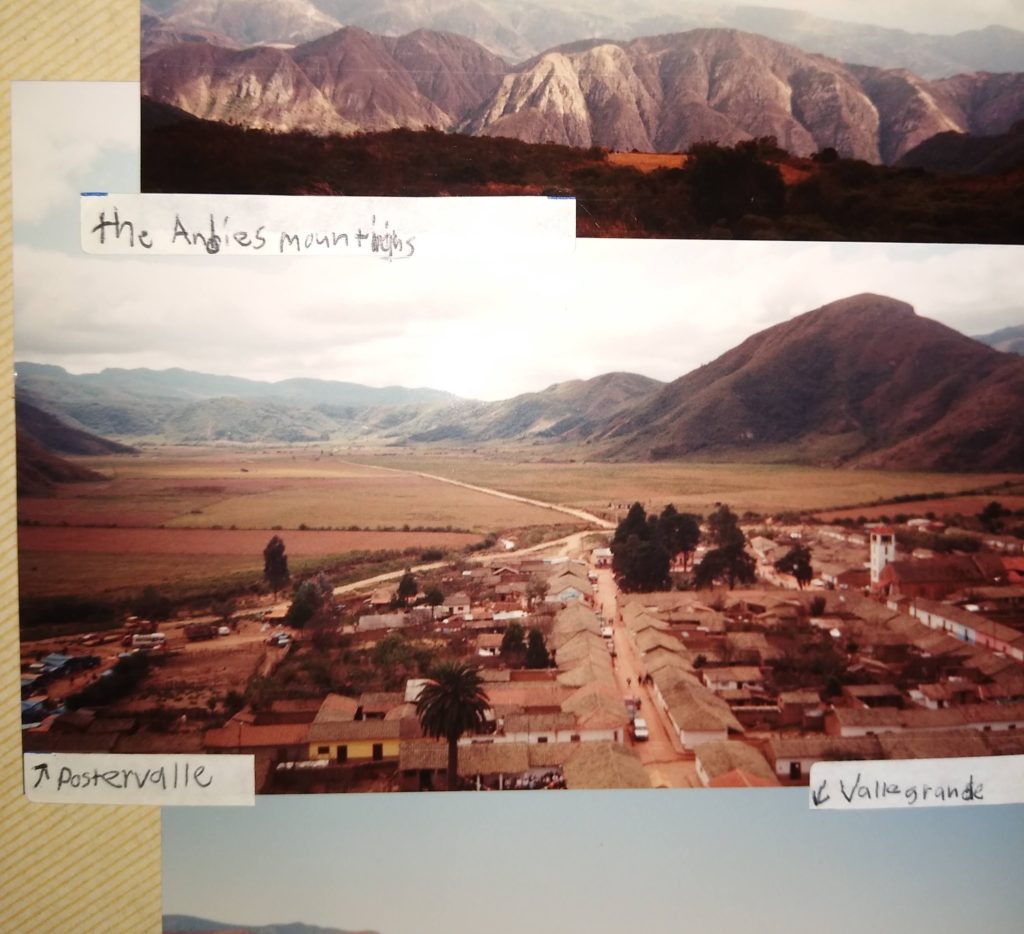

My thoughts take me to 1999. I’ve written about Bolivia a couple of times. But long before I lived there as a high-energy, guitar playing 18-year-old, my entire family spent a month in the town of Vallegrande, nestled in the Andes Mountains.

Dad, mom, sister, brother, and I packed up our 90’s clothes. Armed with a sparkling-new Sony Handycam Hi8 camcorder, we flew to the heart of South America. This would be a kind of survey trip to help our family decide on whether or not we would move there and become missionaries. Though life would take us in another direction, that first international trip helped to shape my life.

During our travels, we spent some time in the village of Postrervalle. The name translates to “the last valley.” It’s the end of the line; the quintessential middle of nowhere. Parts of Bolivia remind me of my own home state of Wyoming. It’s arid, desert-like, and has a sort of cowboy feel to it. We traveled there during Carnaval. This custom includes a weeklong celebration of indigenous beliefs mixed with assimilated pseudo-Catholicism. But mostly, it’s an excuse to party. For days on end, the music rarely stops. Alcohol flows. Food stands and vendors line the plaza.

And for some reason, I remember the rain and the mud…

We sit at a small plastic table, huddled close due to the cold. These parts of the Andes Mountains are cool this time of year. I smell the food cooking and have no idea what it is. But when my dad asks if I want the sausages hanging nearby, my instincts scream, “yes!” Soon, a plate of sausage, rice, potatoes, and salad arrive and I tuck in neatly. Even though I’ve been stuffing my face with candy, I can always still eat. My chocolate supply is running low. Earlier I bought a handful of chocolate sticks (which taste like low quality Easter chocolate) with little comic strips inside the wrapper. I clean my plate, but don’t eat my salad. Our family stays away from the produce. Dad says it’s because we don’t want to get sick. Fine with me. I didn’t want to eat my salad anyway. I’m 12. I want chocolate.

I finish my food and look out to the street. It’s only 4 p.m. and already dark. Actually, the whole day has been dark. The surrounding mountains hide the sun earlier than the true sunset. Above, black rain clouds mask the only remaining light. The foreign festival gives me an uncomfortable feeling.

Darkness sits in this valley like the smoke of a smoldering fire.

The day’s drizzle seems to have stopped, but the mud prevails. Our chilled bodies warmed, we walk down the muddy street laden with trash and running chickens. I remember the story that my dad’s friend told us around a bonfire last night. Apparently, the locals think that the house in which we are staying tonight is haunted. He talked about people hearing things in that house—sounds of strangers dragging one foot. That sort of thing. I don’t buy it. At least, that’s what I want everybody to think. In a place like this, who knows. Postrervalle used to be spiritually dark—witches and demons dark. That is, until he and his mission’s team brought the light of God. And that light has shone in the darkness since. But on a rainy day with foreign music and muddy roads, my mind tingles with hesitant curiosity.

Haunted, you say?

It’s night. I’m lying in a sleeping bag on a straw mattress in the haunted (?) house. Though we’ve all been in bed for hours, I hear the throbbing of the drums and the beating of the music in the town plaza. They’re celebrating. On and on they’re celebrating. And to me, every beat sounds like a stranger dragging his leg. I finally fall into a restless sleep, tossing and turning with the twisted dreams of an imaginative 12-year-old.

But now it’s morning. The sun is shining. I look outside and see that it doesn’t look all that dark anymore. The mud still cakes the roads, but the music doesn’t play. I throw my sleeping bag and backpack into the rusty Toyota pickup. I eat some bread and a chunk of cheese as I climb onto the truck. And rolling down the muddy road home, I glance back at Postrervalle—that last valley. The end of the line.

You know what?

Now it doesn’t look all that bad.

But I know that night will come once again. The drums will beat. And then, at least in my mind, the ghosts will come out to play. The only cure for this darkness is the light.

I’ve been back to that village in the years following my first visit. And though the light continues to seep through the cracks in that dark place, the work in Postrervalle is far from over.

But that was over 20 years ago. Who knows what goes on now in the mountain village of Postrervalle, Bolivia?

anthony forrest